Robot Evolution

Robot Evolution is an application that uses genetic algorithms to evolve and optimize virtual walking poly-pedal robots. The robots are 2D geometric constructions of rectangles that are connected by virtual motors which apply torque to these rectangles, making them move.

In this post I wont really explain how genetic algorithms work nor go into detail about our application, but rather just gloss over the most important features, present some results, and explain them.

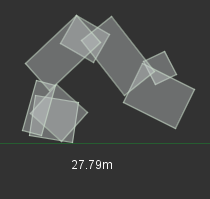

Here’s an example of an evolved galloping robot:

The application was developed by Jan Corazza (blog author) and Luka Bubalo.

Some of the features include:

- Optimizing robot walking capabilities

- Visualizing evolution in real time

- Interactive UI

- Parallelizing simulations

- Persisting results

- Rich configuration

I’ve also made a neat logo for it:

Most importantly, we’ve severely tightened our problem space to walking robots only. The reason for that was because the deadline of the competition we’ve been aiming at was getting really close, and of course as we’ve started designing the details of the application, it became increasingly apparent that we wouldn’t be able to meet the deadline with such an enthusiastic approach.

Thus, it was decided to switch the language from C++ to Java, in addition to the above restrictions on the scope of the project. However I still believe that’s only the natural evolution of an idea.

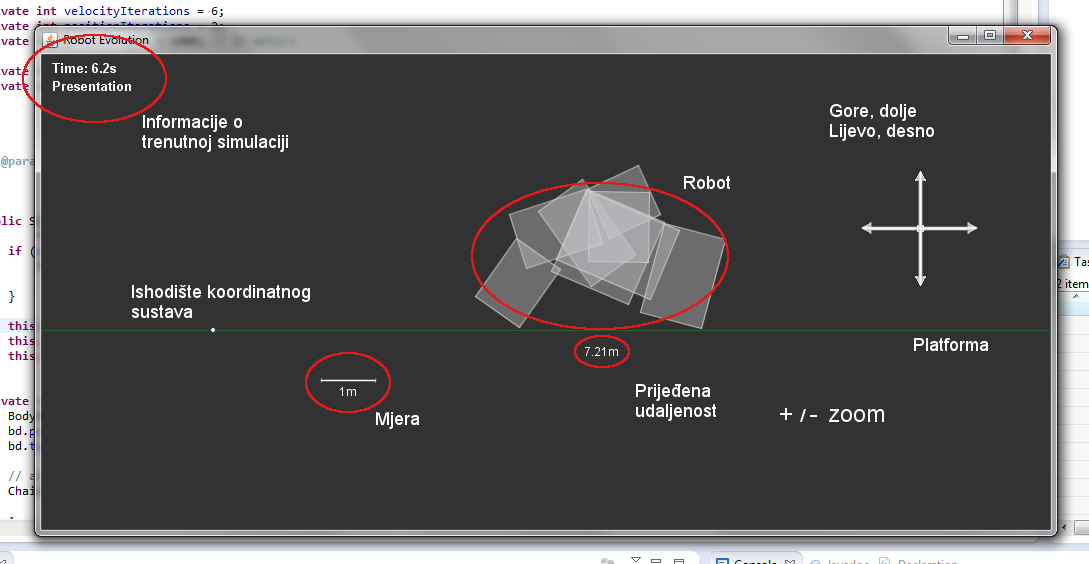

This is the GUI of the application:

But it can also be ran on servers:

The configuration is done via a Java properties file which provides for really simple key-value bindings that the application can natively read. Here’s an example of a configuration file:

#evolution

generations=50

robotsPerGeneration=100

mutationChance=0.1

#simulation

robotSeconds=240

parallelSimulations=5

gravity=9.81

#mode

GUI=true

save=last-example

load=false

#visualization

windowWidth=1024

windowHeight=512

pause=0

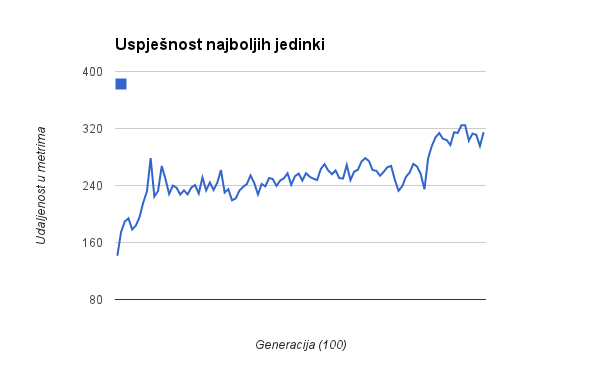

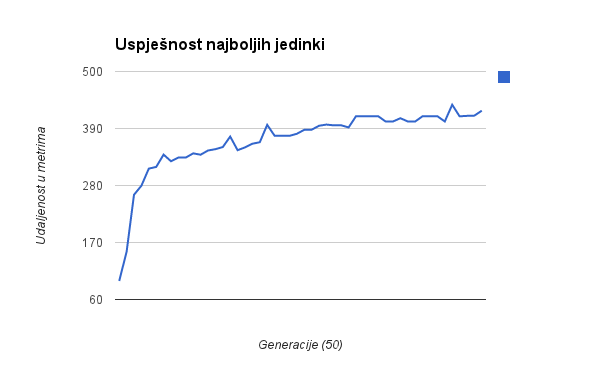

Here’s some data we collected recording the performance of the fittest unit (robot) in each generation (performance is measured in meters passed):

- Performance of the fittest robots over 100 generations

- Performance of the fittest robots over 50 generations

Evidently performance increases with the number of generations.

The different levels of intensity in random fluctuation in these graphs are due to different selection mechanisms, used to promote units from one generation to the next one.

The first graph shows the usage of plain proportional selection (also called roulette wheel), which makes the chromosomes from a previous generation proportionally present in the current one according to their fitness. For example, if a unit accounted for roughly 50% of overall distance passed in a population (an obviously superior robot), then the algorithm would assign each new unit a chance of 50% to have it as a parent – thus, instead of there being only one sample, roughly half the units would now inherit from the superior one.

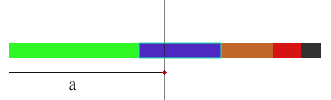

The method of proportional selection can be illustrated like this:

- a is a random number, the colored cells represent units, and their length is proportional to the fitness of the unit

The reason proportional selection seems to fluctuate so drastically is the fact that the method does not guarantee that a fit unit would be represented at all in the following generation – there are merely higher and lower chances, but no guarantees. In the above example of a superior robot, it would be completely possible for it to not be included at all (and usually the chance for that is very high since no unit actually has 50% of the population score, but rather around 1/(number of units in generation))! We will try mitigating this effect by increasing population sizes.

The second graph is an example of a hybrid selection mechanism – combining truncation selection and proportional selection. This method guarantees that the top 10% will always pass on to the next generation (truncating the top), thus reducing the fluctuation effects only to minor mutations. The rest of the 90% of the generation gets filled proportionally.

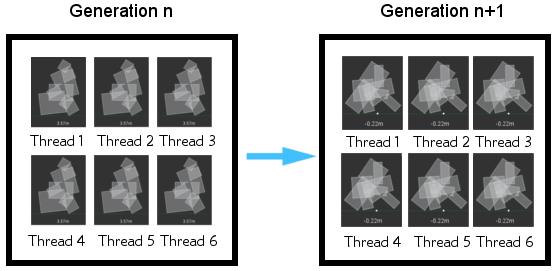

The actual evaluation of the fitness is a rather delicate procedure, from my perspective at least. The entire population is divided into N simulations, and each simulation is independent from the other. The simulations are then parallelized and left alone to crunch numbers with the physics engine JBox2D. After their calculations are done, the results are aggregated together, so the next generation can be computed (using the above selection mechanisms).

Parallelization can be visualized like this:

As the image demonstrates, threads are recycled between simulations. It’s also important to note that it is not possible to concurrently compute two different generations due to the fact that each generation is conditioned by the one before it (with the exception of gen #1 which is randomly generated).

The main thread takes the most successful unit from the last generation and creates a another sandboxed simulation for it. This simulation is presented to the user in real time, and its results are discarded (i.e. not measured at all).

We use tools from the Java Concurrent package for parallelization, and Swing for 2D graphics and the UI.

Robot Evolution is free and open source software under the MIT license.

Relevant links:

The download folder has the source code (use GitHub though, as it’s guaranteed to be the most recent version), and a 7-zipped file containing the runnable JAR (with all the dependencies) and a configuration file.

Run the program like this:

java -jar rtevo.jar configuration.properties

You can edit the configuration file to suit your needs.