A game in a pure language (part 1): introduction and problems with Idris

At the beginning of 2019, I started working on my most ambitious project yet: a video game in Idris, a pure functional language with dependent types. I picked Idris for two reasons: (1) because I wanted to learn the language as it seemed amazing, and (2) because I was sure that making a game in a pure language was bound to present interesting problems. So far it’s been an amazing journey (albeit frustrating at times): somewhere around 13k lines of Idris code, along with trace amounts of C and C++ needed for some bindings; a number of somewhat-working game systems, one complete rewrite…

However, I seem to have come to an impasse. I definitely learned a lot about Idris, functional programming, and leveraging type systems in the context of an extremely stateful and interactive system. At the same time, the idea for the game itself really grew on me, and it had become apparent that my lack of experience in this field, along with some things that are obvious impracticalities of Idris development, were a very real hinderance in executing this project.

Nevertheless, I’ve really fallen in love with Idris, and many of these problems have little to do with its essential nature and more with it still being in early stages of development. I hope you’ll consider trying it out, and I recommend Edwin Brady’s excellent book, Type-Driven Development with Idris. I think every programmer that cares about safety and correctness should read it, it covers a lot of ground from the basics of Idris to implementing state-aware and concurrent systems, and the exercises are fun. Of course, I also want to warn of the major roadblocks that I’ve stumbled upon.

This is the first post in what will hopefully become a series about my experience with this project thus far. I’ll talk some about the game itself, and the various challenges that spring up in programming a game in a pure language.

A short note on Idris

Just like functional programming encourages you to express functions on the fly, dependent typing and first-class types expand those ergonomics up to the type level, allowing you to compute types. This is a huge deal when it comes to verifying that your programs are correct, because you can express certain properties in types that you otherwise couldn’t, which the type-checker will then make sure are satisfied.

Here’s a canonical example that anyone who’s heard of Idris has seen a million times already:

-- [1, 2, 3] ++ [4, 5] = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

(++) : (xs : Vect m a) -> (ys : Vect n a) -> Vect (m + n) a

(++) [] ys = ys

(++) (x::xs) ys = x :: xs ++ ys

The first non-comment line is the most important one, especially Vect (m + n) a. The + there is just a simple addition operation that works with natural numbers! And n and m are similarly also just natural numbers. What’s so special is that such elements can now appear in types, meaning that if your implementation were to, say, drop some elements, it would no longer type-check, and so an even greater class of bugs are caught statically. (Dropping elements is not a great example because the more relevant use of this type constraint is to guarantee certain properties of ++ to other functions, but I digress.)

Sadly I didn’t manage to make as much use of this type-level programming as I had hoped I would at the beginning: Idris allows you to gradually refine your types, and I’ve often succumbed to just moving on to the next feature as my interest for the game itself grew. Regardless, my understanding on that front is progressing, and there were indirect benefits especially in the department of state management (I didn’t have to write my own proofs in order to benefit from proofs which were already written about the elements I was using).

Type-driven development

One of the best aspects of Idris is type-driven development. The essential idea is that when writing your functions, you start from the types, which you gradually refine, and you have the compiler fill in as much code as possible on your behalf. Writing Idris should ideally be an interactive process of talking to the compiler:

The compiler knows that the Expr type comes in four variants and can automatically split your function implementation into all possible cases depending on the variant of the argument. In fact, because of dependent types, this doesn’t only concern the “form” of the argument, but all aspects of its value as well. When splitting the ++ function, the cases would be [] and (x::xs) as above, and these branches contain the information about the type of the argument: in the [] case, we know that xs : Vect 0 a.

The parts that look like ?this are called holes, and since they are typed you can use them to guide you in implementing the rest of the function. This is more handy than it sounds: in Idris, an unexpected amount of information hides in the type, and the types of holes can tell you things like “you’ll need to close this resource before continuing” or “you can’t access health information in this part of code”. Sometimes, the holes can be automatically filled in based on the available information alone.

Now, a few words about the game itself.

It’s a 2D RPG / action platformer with a focus on physics

My main goal with this game is to make the combat fun. I dislike RPGs where you merely unlock progressively more powerful skills, which in the end amount to simple damage multipliers. I also love visual dynamism, but dislike when it’s treated as merely purposeless fluff (such as having enemies fly away with ragdoll mechanics when killed, but in a way that the effect is neither impacted by the severity of your actions nor is able to affect other objects on the scene, reducing the physics of the event to a mere animation). In WoW, when you shoot an arrow at an enemy, an animation will just chase them no matter how they move, and when it hits it will do some damage and/or apply an effect. Other games tend to do better these days, giving you an option to actually aim your hits, but the improvement rarely goes beyond that, and the number of interesting moves you can pull off remains relatively poor (there are exceptions, such as Dark Messiah).

In order to enable actually interesting skills and events, I’m basing the entire game on Box2D, a physics engine which allows you to simulate the movement and dynamic interaction of objects with various shapes and connections, set forces on them, detect collisions, and much more. The idea is that, in a given moment during combat, the main source of interesting situations are not the rules and the numbers behind some scene, but rather the mechanical interactions and events that you can cause, influence, benefit from, or get hurt by as the player. Effectively; skills, spells, effects, etc. are expressed in terms of actually-existing physical objects on the scene, the forces between them, various configurations in which they can be bound (like joints, chains, and so on). This can only be taken so far, of course.

Here’s a couple of examples:

| Instead of a spell/ability that | you’d have a spell/ability that |

|---|---|

| gives your projectiles 2x damage | makes your projectiles slightly faster |

| makes you evade projectiles | creates an antigravity field around you |

| does area-of-effect damage | pulls together objects and makes them explode |

| adds some effect on melee hit | knocks back the enemy |

And so on. There is more, in the sense of combining your abilities with the environment: braking chains to make complex structures collapse, freezing the floor to lower friction beneath some enemies and knock them back, or varied forms of transportation/mounts enabled by the deep integration of physics into the game mechanics. Of course, predictability and rules are on some level necessary, but the point here is to move that level lower.

Another major part of the game that I want to get right is, well, the RPG aspect. Going off from the same starting criticism of classical RPGs with their predetermined progression systems, the idea again is to increase the number of combinations and make crafting your class an integral part of play. But this part isn’t really fleshed out yet and it’s best to leave it for another time when I’ll talk about the game in more depth.

These aren’t really new ideas, and there have been games that executed both the combat and the RPG aspects way better than I could. They aren’t clever or innovative gameplay gimmicks. It’s just that I have identified this combination as the game that I’ve spent a lot of time searching for and never managed to find. A game you can engage in short bursts while still progressing towards long-term goals, and where this progression rewards you not just in virtual numbers but in more possibilities and varied combat.

What was made so far

-

basic level editor

- scripting engine

-

scripts can be programmed in a makeshift DSL:

doDamage attacker target for sound = with RuleScript do UpdateNumericProperty target "health" $ waste for playConditional attacker sound Just health <- QueryNumericProperty target "health" $ current | pure () case health <= 0 of False => pure () True => Output $ Death targetThis was really fun to make, and as with most things here, I’ll explain what’s happening in more detail later

-

it can also execute behaviors, which are JSON-defined state machines:

"chase": { "onTime": { "time": 5, "time_parameter": "chase_duration", "transition": { "state": "roam", "actions": [{"type": "end chase"}, {"type": "stop"}, {"type": "begin walk"}] } }, "onHit": { "transition": { "state": "chase", "action": {"type": "begin chase"} } } }

-

-

Box2D physics ontop of my bindings for Idris (note: abysmall code), along with relatively smooth movement, discriminatory/filtered collision detection, and an event system that is integrated into the scripting engine (e.g. the ability to write queries for objects around some place and place handlers for them, or handlers for certain kinds of collisions)

-

very rudimentary UI system

This is also used in the level editor. The views are described via JSON, but they’re also sometimes created programmatically

-

animation system on top of Idris SDL2 bindings which I’ve slightly modified

-

descriptions of game entities such as maps, objects, behaviors etc., which can be read from and saved to JSON files

ObjectCaster MapDescription where objectCast dict = with Checked do name <- getString "name" dict dimensions <- getVector "dimensions" dict -- ... Serialize MapDescription where toDict md = with ST do mdObject <- makeObject addString mdObject "name" $ name md addVector mdObject "dimensions" $ dimensions md -- ... -

the basics of the item/inventory and ability systems

- various details like saving, switching levels

Obviously lacking: any kind of content, and most of the actual systems that the player interacts with.

Lastly I’m going to summarize some problems that I’ve had with Idris:

Problems with Idris

Some of these issues are probably actionable, I wish I had the time and will to actually document them properly and report them to the maintainers, and maybe help a little in getting this awesome language more traction in the mainstream.

Note that I’m writing this from the perspective of an Idris (and fp, really) novice.

1. Compile times

As I’ve said, Idris is supposed to be developed interactively with the compiler helping you along the way by:

- providing type information about a variable or a hole (along with context information for holes, that tell you the types of variables available at that point)

- doing case splits

- inserting

withpatterns/views and match expressions (i.e. turning a hole into them) - searching for values to fill holes (proof search)

- displaying docs for a symbol

- just typechecking the whole file and reporting errors

These are usually key-bound actions in your editor. They require that the file you’re working on, and all files it depends on, be saved, compiled, and have the results loaded into memory. Additionally it seems to me that the current file is always recompiled (apparently even for a :doc operation), while others are only recompiled when they had changed.

The problem? This can take almost a minute on a file with >250 lines. Compiling the entire game:

$ time make

...

real 8m28.996s

user 0m0.015s

sys 0m0.015s

Basically, forget interactive editing, the meme of making coffee while the code compiles lives on!

There are probably some aspects of my code that worsen this problem, such as liberal use of do notation and overloaded >>=, but they’re still basically things you’d encounter in most real-world codebases, and the worst case is an important reference point.

A related problem is memory usage by the IDE integration of idrisc. There’s a memory leak and I could only do like 15 actions before I had to restart Atom!

2. Bad error messages

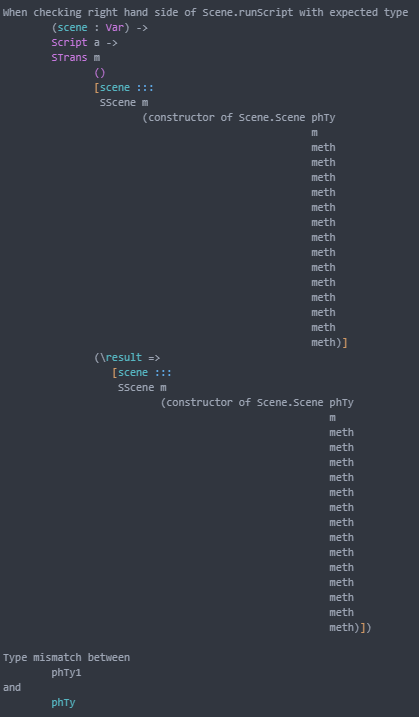

Bask in this glory:

This one seems OK on first glance until you realize it’s warning you that there’s a mismatch between two identical things:

Oh, you probably want to enable showing implicits… maybe? Here you go:

Okay, enough snark. This is a genuine problem. As soon as you’re working in a context like ST, the main state management facility I’ve used, you can pretty much forget about error messages being useful most of the time. They really do look similar to the above. That isn’t the only place where error messages fail the user, just the most frequent one. Often, the compiler will complain about something in a roundabout way, and you’ll be forced to read its mind and conclude that, no, there really wasn’t a type error in your code, you just forgot to export some function from another file.

Sometimes they can be impressive:

Here you are told that you’re not allowed to execute some operation because you’re in the wrong state. This shows how much potential Idris has.

3. Rough edges around organizing stateful code components

I will definitely sing praises to Control.ST later on, however, it sometimes seemed prohibitively inflexible. Already mentioned: weird error messages.

But what’s more important is that there seem to be way too many instances where the compiler is just unable to figure out something that from all I can tell should be possible.

One of the main apparent failings is sending Vars around, which are values that represent a resource (such as an SDL renderer). You usually organize functions that operate on a common resource under an interface, but I just couldn’t figure out how to write a function in such an interface that accepts two Vars. For example, both the Client and Server systems rely on the Dynamics system: the server should own one to send authoritative updates to the client, while the client should also own one in order to interpolate the game between server updates. However in single player mode, there is no need to duplicate this work, and naturally you’d only spin up one instance of Dynamics, and allow both the server and client to access it. However, this seems to be impossible, and you have to rely on indirect ways of getting the relevant information in and out of the dynamics system.

This kind of inflexibility popped out often and was the most annoying thing with Idris. A part of the reason is certainly the fact that I don’t understand this territory all that well. It’s possible that ST afforded me too much comfort and that as a result I sometimes descended into a reflexively imperative mindset, leading to bad approaches to the design problems I was facing. However, ST really does seem to be the best way to create stateful systems in Idris, and since the language is so new I was basically unable to figure out whether there were better approaches (given that I wanted to actually complete the game and had other time constraints). Rather I was forced to create somewhat hacky solutions.

4. Installation

Almost every attempt to install Idris on another machine and get my game to compile and run was a trip to literal hell. I’m pretty sure most of these attempts failed. At one point I was even looking at GHC source code, you shouldn’t have to do that unless you really want to!

5. The damned implicits

In Idris, functions can take implicit arguments, a near-essential feature. A function such as:

index : Fin n -> Vect n a -> a

already has two implicit arguments: n : Nat and a : Type, so its full definition is really:

index : {a : Type} -> {n : Nat} -> Fin n -> Vect n a -> a

However both when defining and when calling functions, implicit arguments are often as their name suggests left implicit: inferred by the type checker or supplied by the environment (often you say auto prf : something to make the type checker search for a proof of something, like a list being nonempty, at the call spot).

Ideally, you’d expect to provide implicit arguments explicitly only when something has to be disambiguated. I realize this is the ideal, however the sheer frequency of cases where you have to explicitly specify them is a stumbling block and a cause of failed type checks.

For example, I still don’t know why I had to put {m}s there on the last line here:

renderBackground : (SDL m, GameIO m) =>

(map_creator : Var) ->

(sdl : Var) ->

(camera : Camera) ->

ST m () [map_creator ::: SMapCreator {m}, sdl ::: SSDL {m}]

This merely brings the implicit m argument in scope and then specifies that the same one is to be used for SMapCreator and SSDL. Remove this and you get a weird error that doesn’t really tell you what’s wrong, and can cause you to look elsewhere before you remember to check for this. In time, you learn to anticipate this and not make the mistake, but sadly similar issues can pop up elsewhere.