Reinforcement learning, non-Markovian environments, and memory

I recently finished reading a reinforcement learning textbook (by Barto and Sutton), and throughout it I was constantly vexed by one important assumption that underlined all the algorithms: the Markov property, stating that a succeeding event depends only on the one preceding it, and not on ones far in the past. This kind of restriction is a helpful tool both practically and theoretically, but it causes problems when dealing with a rather natural situation where there is long-term dependence between events. The book doesn’t address this, so I tried to, and found out it’s a genuine problem with real research behind it. Here’s what I did.

And here’s the Rust code I wrote that includes several algorithm and environment implementations taken from the book and also my method for this dependence problem.

But first, a brief explanation of the basic concepts:

The basics of reinforcement learning

The point of RL algorithms is to learn a policy (for achieving some goal) from interacting with an environment. A policy is a mapping from states to actions (or, a mapping from actions to probabilities of taking them in some particular state), which is followed by an RL agent. The interaction consists of the agent taking actions which causes the environment to undergo state transitions and provide the agent with a reward signal evaluating its performance in achieving the goal. The point isn’t chasing after immediate rewards, but maximizing overall cumulative reward (or gain) from the interaction.

Many tasks can successfully be formulated in this framework: a game of chess where all moves give a reward of 0, except a win resulting in a reward of 1 and loss resulting in a reward of -1 (a draw also being 0).

The algorithms accomplish policy improvement indirectly by estimating the value of the environment’s states (or (state, action) pairs), and modifying the policy to better reflect that knowledge. Value is defined as the gain (cumulative reward) following a state (or state-action pair). If you are in state S_t with available actions A1 and A2, then knowing that the state-action pair (S_t, A1) is more valuable than (S_t, A2) should be reflected in your policy so that the probability of taking A1 is no less than the probability of taking A2.

This incremental process is called Generalized Policy Iteration and is a strong contender for the core idea of reinforcement learning. It actually consists of two competing processes:

- Policy evaluation: for a given policy, estimate the values of states or state-action pairs for the agent following that policy (i.e. learn the value function of the policy)

- Policy improvement: for a given value function, change the policy so that it is more likely to result in more valuable behavior (e.g. by making it greedy with respect to the learned value function)

An important theoretical result that enables this is the Policy improvement theorem, which justifies the policy improvement step. It assures that the resulting policy is either strictly better, or that the original policy is already optimal. (There’s some very interesting math here derived from Bellman optimality equations, but I won’t get into that here.)

Another important idea is that the crucial problem all RL algorithms solve can be thought of as credit assignment, i.e. giving credit for future outcomes to past behavior.

The Markov property and breaking it

The interaction process is a sequence of random variables: (S_0, A_0, R_1, S_1, A_1, R_2, ...) called a Markov decision process. This is where the Markov property comes into play: it is a restriction on the environment/interaction dynamics stating that the probability of the next state and reward is a function of the previous state and action taken. The only information that determines the probabilities of transitioning into S_{t+1} with reward R_{t+1} is the pair (S_t, A_t) (these probabilities usually aren’t known, however).

The restriction is worthwhile: it underlies the convergence proofs for estimating values and guarantees that policy iteration is possible and finds the optimal policy in the limit. Many examples of environments satisfy the Markov property so you can still get far. It also guarantees that it is possible to encode knowledge about values of states and actions “locally”: that we can rely on the gain following a taken action to really be due to that action, and not some past one. The relation to the credit assignment problem is obvious.

But it is also a genuine restriction that bothered me while reading: it’s not difficult to come up with meaningful tasks/environments where the Markov property does not hold. After finishing the book I wanted to see how hard it would be to modify the algorithms to handle credit assignment in these non-Markov environments. First, here’s an example of such a case:

The task here is simple. There is a corridor that ends with a choice: up or down. On each trial, one of these paths is randomly trapped, meaning that taking it results in a large negative reward (the other path gives a positive reward). All other actions give a small negative reward to incentivize moving forward. The crucial part is that the location of the trap is observable but only at the start of the corridor. Afterwards, this information is unavailable.

Why does this break the Markov property? Because in the final state i.e. the “split” where the up/down decision has to be made, the reward probabilities depend on the starting state, i.e. on the observation made there. The choice “up” doesn’t have a set of probabilities for receiving rewards, but rather the probabilities are a function of what the agent had observed sometime in the past. The knowledge of the value of available actions cannot be encoded locally at the split state alone.

This is the general form of many of these Markov-breaking examples: long-term dependence of future events on past events. And none of the algorithms from the book can solve this example, even though it seems to correspond to a reasonable task.

The solution

I came up with a simple solution and it works, although only if certain requirements are met by the algorithm. Later I found out that people already worked on this problem (of course), but I’m still glad I independently identified it and had a working solution.

The solution is giving agents a few bits memory and actions for mutating them. In fact, for the corridor problem, a single bit will suffice. But this has to be done transparently, with minimal changes to the algorithm itself. More precisely the agent should have its (state, action) pairs extended at each step: the state S_t becomes (S_t, MS_t) and the action A_t becomes (A_t, MA_t), where MS and MA denote memory-state and memory-action. Effectively this means that you can take a regular RL algorithm and give it, in each step of the interaction, the ability to read and write to memory M (which can generally be a bit array), and M becomes a part of the environment state from the perspective of the agent–this is how the “transparency” is accomplished. The reading and writing of memory has to be completely subject to learning.

How can this solve the corridor problem? Well, for one, now it is at least possible to have a policy that solves it! The policy is simple: in the beginning, depending on the observation that tells the agent where the trap lies, either flip the bit or don’t (it starts in 0, always). Afterwards, don’t touch the bit (noop). Then, at the split where the up/down decision has to be made, your state is no longer S_t=Split, but (S_t, M_t)=(Split, m), and m tells you the observation from the past! The policy at this stage has encoded the value for going up or down that is dependent on the memory set at the beginning: we’ve handled temporal dependency between the observation event and the decision event.

But the harder question is: can this policy actually be learned?

The limitation

To understand when this policy is learnable and when it is not, and why, it is best to look at the simplest RL control algorithm, SARSA, named after the basic segment in a Markov decision process (S_t, A_t, R_{t+1}, S_{t+1}, A_{t+1}). There’s no need to spell it out in detail, it only has two crucial parts corresponding to the two competing processes in Generalized Policy Iteration. Here, Q(s, a) denotes the state-action value function that the algorithm is learning, and epsilon-greedy means choosing an action that is best according to Q most of the time (with 1 - epsilon probability) and a random action some of the time (with epsilon probability).

For each step of the episode:

- From

S_ttake actionA_t, observe transition toS_{t+1}with rewardR_{t+1} - Choose next action

A_{t+1}so that it is epsilon-greedy with respect toQ(policy improvement) - Update

Q(S_t, A_t)slightly towards a new target valueR_{t+1} + Q(S_{t+1}, A_{t+1})(policy evaluation)

The update target is the most important part: R_{t+1} + Q(S_{t+1}, A_{t+1}) is a new estimate of the gain following S_t after A_t is taken, and what’s interesting is that it only takes into account the immediate reward and not rewards that come afterwards. However gain isn’t just the immediate reward: it is the cumulative reward, i.e. the sum of all rewards. Correcting that is the role of the Q(S_{t+1}, A_{t+1}) term, the value of the succeeding state-action pair. As I said in the introduction, value functions represent the gain following a state-action pair.

My Rust code for SARSA is here, it has more details.

Can this algorithm learn a policy that solves the corridor problem? Well, no. Too bad! Why? Because of the credit assignment problem. The algorithm cannot give credit to the action of remembering the observation because it only gives credit one step backwards! Here’s an illustration:

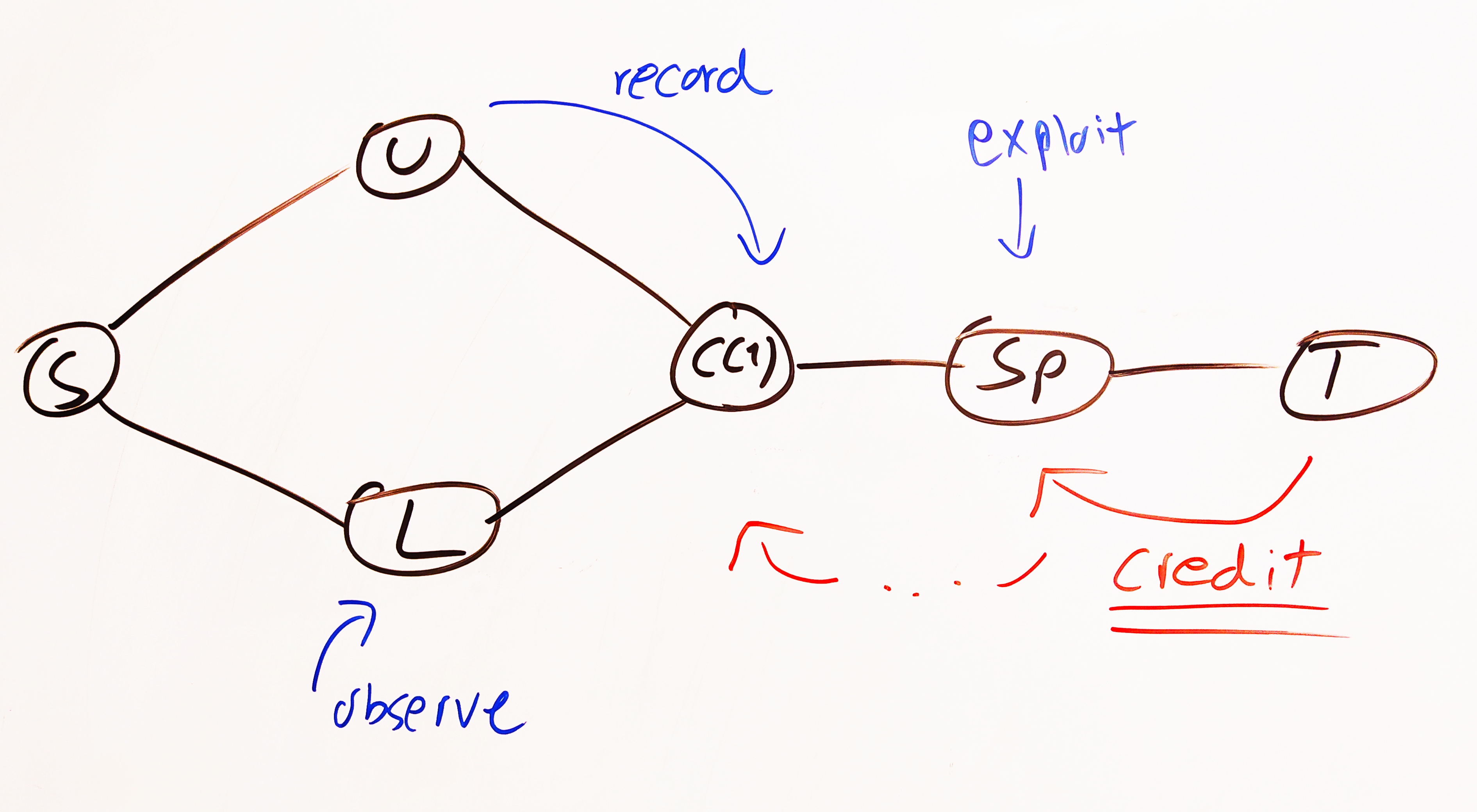

The agent moves from S into either U or L and this state represents the observation. Then it moves into the corridor C(1) (there can be multiple corridor steps afterwards, C(2), ..., C(n)), and on this move is free to record the observation into m. Finally it reaches Sp (split) where it can make its choice and receive the final reward depending on its choice and its past observation. SARSA simply isn’t able to credit that crucial transition U/L -> C(1) where the recording could’ve taken place. So its performance will sadly always be 50/50.

Not all is lost

Thankfully, there are RL algorithms that are smarter about credit assignment! There are Monte Carlo methods, which wait for the entire episode to finish before updating estimates for all state-actions. They also have the benefit of knowing the actual return that followed each one. One of their drawbacks is that they’re incapable of online learning.

There’s also n-SARSA! It’s the SARSA algorithm, but expanded so that it records the last n transition and assigns credit accordingly, not just using information from the last step. The book points out how SARSA and Monte Carlo are actually just extremes of the n-SARSA continuum.

That’s just what’s needed: an algorithm that looks into the past far enough so as to be able to credit the decisions made back then.

I implemented n-SARSA too, Rust code is here, and that’s the one I used for this problem. Here’s a sample episode after the learning was done:

S: (Start, 0), A: (Forward, Noop), R: -5

S: (ObserveL, 0), A: (Forward, Flip), R: -5 --- Lower is trapped (flip the bit)

S: (Corridor(1), 1), A: (Forward, Noop), R: -5

S: (Corridor(2), 1), A: (Forward, Flip), R: -5

S: (Corridor(3), 0), A: (Forward, Flip), R: -5

S: (Corridor(4), 1), A: (Forward, Flip), R: -5

S: (Corridor(5), 0), A: (Forward, Flip), R: -5

S: (Corridor(6), 1), A: (Forward, Flip), R: -5

S: (Split, 0), A: (Up, Noop), R: 100 --- So go up

Gain: 60

And here’s one where U was observed:

S: (Start, 0), A: (Forward, Noop), R: -5

S: (ObserveU, 0), A: (Forward, Noop), R: -5 --- Upper is trapped (don't flip the bit)

S: (Corridor(1), 0), A: (Forward, Noop), R: -5

S: (Corridor(2), 0), A: (Forward, Flip), R: -5

S: (Corridor(3), 1), A: (Forward, Flip), R: -5

S: (Corridor(4), 0), A: (Forward, Flip), R: -5

S: (Corridor(5), 1), A: (Forward, Flip), R: -5

S: (Corridor(6), 0), A: (Forward, Flip), R: -5

S: (Split, 1), A: (Down, Noop), R: 100 --- So go to down

It works! Always. Here’s the full value function learned by n-SARSA.

The core idea here is to make the algorithm learn how to interact with its memory as well as with the environment. A single bit is a simple, stupid solution, but it works on a simple decision with temporal dependence problem. I googled around and found a paper that trained LSTMs for this purpose: I haven’t read it yet but I believe that it corresponds to this same basic idea, it’s just a much more sophisticated architecture.